People Are ‘Disappearing’ Since Trump Took Office. Here’s What That Means.

Enforced disappearance functions as a tool of terror in two ways.

Last month, Venezuelan asylum seeker Frazieralth de Jesús Cornejo Pulgar was scheduled to appear in immigration court for a routine hearing.

But as Mother Jones reported, he failed to appear because he was taken without due process to El Salvador’s Terrorist Detention Center (CECOT) along with 230 other Venezuelan migrants. (Cornejo Pulgar, who has no known criminal record in the United States or Venezuela, was reportedly detained because of his tattoos.)

Since President Donald Trump launched what he called the “largest deportation campaign” in U.S. history earlier this year, there have been numerous cases of disappearances of migrants like Cornejo Pulgar.

In January, Ricardo Prada Vásquez, a Venezuelan delivery driver and McDonald’s employee in Detroit, Michigan, was deported and “disappeared” in El Salvador after taking the wrong route to Canada.

Ben Levy, an attorney at the National Immigrant Justice Center who is trying to locate Prada-Vasquez, told the New York Times: “Ricardo’s story is tragic in itself, and we don’t know how many Ricardos there are.”

ICE agents eventually confirmed to Levy that the 32-year-old had been deported, but without revealing his destination. After kidnappings, families of men like Prada-Vasquez search for their loved ones, but their names disappear from ICE’s electronic detainee tracking system.

Can the plight of migrants under Trump be classified as “enforced disappearance”? We spoke with academics and researchers who study how rogue states disappear people.

First, what does it mean to “disappear” someone?

According to the United Nations, an “enforced disappearance” occurs when agents of a state (or groups acting with its authorization and support) arrest, detain, abduct, or otherwise deprive a person of their liberty. The state then refuses to reveal the fate or whereabouts of the person.

If you’re wondering whether this is legal or illegal, it’s neither. “The fundamental consequence of an enforced disappearance is that the person is placed outside the protection of the law, in a kind of legal limbo,” explains Gabriella Citroni, assistant professor of international human rights law at the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, and chair-rapporteur of the UN Group of Experts on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances.

Unlike other crimes under international law, such as torture, enforced disappearances were not prohibited by a binding universal legal instrument before the UN Convention came into force in 2010.

Citroni added that disappeared persons often include political opponents, protesters, human rights defenders, community leaders, students, and members of minority groups.

“Enforced disappearances are generally used to suppress freedom of expression or religion, to justify civil conflicts calling for democracy, as well as against people engaged in the defense of territory, natural resources, and the environment, and to fight organized crime or terrorism,” she added.

Oscar López, a Mexico City-based journalist working on a book on the origins of enforced disappearances during Mexico’s “Dirty War,” said that enforced disappearances are used as a tool of terror in two ways.

“First, the victim is deprived of due process and is often subjected to torture, in addition to the psychological anguish caused by not knowing their fate and potentially fearing for their life,” he told HuffPost. Second, enforced disappearances plunge families and communities into painful uncertainty, López explained. “They don’t know if their loved one is alive or dead, and they oscillate between desperate hope and unbearable despair.”

Lopez said that repeated disappearances can plunge entire communities into a state of terror, uncertain of the fate of those who will be abducted again.

What has happened to disappeared people in the past?

Lopez said the fate of those forcibly disappeared depends “hugely on the context” in which they were abducted. But generally, if a person is kept alive, they are held by the state indefinitely, without access to family or legal counsel; in other words, “held incommunicado.”

If a person is killed, their body is often disposed of in a way that makes finding them nearly impossible.

“That can mean burying them in unmarked graves, cremating them, or, as has happened in Latin America, throwing them into the sea,” he said.

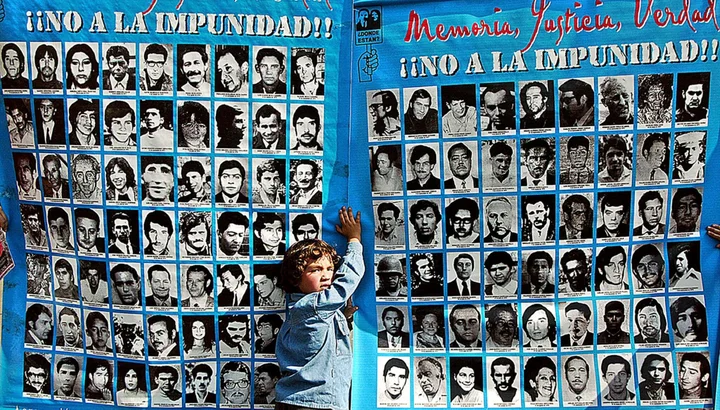

Where have enforced disappearances already taken place?

Lopez cited a few examples: in Argentina, during the military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983, an estimated 30,000 people disappeared. In neighboring Chile, more than 1,000 people disappeared under Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, while in Guatemala, some 45,000 people were victims of enforced disappearances during the civil war that lasted from 1960 to 1996. In North Korea, enforced disappearances and kidnappings date back to 1950.

“There are also more recent cases of enforced disappearances. In Syria, for example, an estimated 136,000 people disappeared under the Assad dictatorship,” he said.

But enforced disappearances aren’t always the work of state agents, according to Adam Isaacson, head of border and migration issues at the Washington Office on Latin America.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been victims of enforced disappearances in Colombia and Mexico, operating with the tacit approval, or even assistance, of government officials.

“Sometimes, as with anti-communist paramilitaries in Colombia and death squads in El Salvador in the 1980s, authorities collaborated with these groups out of ideological alliance,” he said. “And sometimes, as with corrupt Mexican police officers aiding organized crime, they do so because they profit from it.”

Can the current situation of migrants in the United States be described as “enforced disappearance”?

Despite court rulings and ongoing legal challenges, the Trump administration is continuing its deportation policy in El Salvador, in partnership with the country’s president, Nayib Bukele.

Venezuelan migrants, in particular, have been targeted for deportation, often based on unfounded allegations of gang affiliation. Yet, Trump has repeatedly stated that he “fully supports” exploring ways to detain American citizens in foreign prisons.

Should the current situation be characterized as “enforced disappearance”? A UN report published in April suggests so.

The report stated that the incommunicado detentions appeared to constitute “enforced disappearance, in violation of international law.”

The UN experts wrote: “Many detainees were unaware of their destination, their families were not informed of their detention or deportation, and US and Salvadoran authorities did not release the names or legal status of the detainees.” They added: “Detainees in El Salvador have been denied the right to contact and visit their loved ones.”

Isaacson agrees that things should be called by their true names here.

“The only difference between this and what happened in Chile or Argentina in the 1970s is that relatives have better reasons to believe that their loved ones are still alive and have not been killed,” he said. But even this certainty is not absolute, he added: “Can you say with absolute certainty that André Hernandez, the gay Venezuelan designer who disappeared two months ago, is still alive today? He may be, but we can’t guarantee it, and no one will.”

The roundups and deportations have sown fear in American communities, another characteristic of enforced disappearances. The Trump administration has explicitly stated that its goal is to make life so difficult for migrants that they “deport themselves.”

Rod Abu Harb, associate professor of international relations and researcher on enforced disappearances at University College London, said the fear of sending prisoners to an infamous El Salvador jail, where they will never see the light of day, contributes to this goal.

“These raids are extremely concerning for undocumented people, even those who are legal residents of the United States: They could be victims of one of these raids, disappear in prison, and be deported to a third country to which they may have no connection,” he told HuffPost.

What can ordinary citizens do about enforced disappearances?

López said the best thing Americans can do to challenge these efforts is to draw as much attention as possible to individual cases.

Whether by organizing protests, creating online petitions, or posting on social media, ensuring that the person the government has attempted to disappear remains visible and present in the public debate can be an effective way to draw national attention to their situation and that of others like them.

Isaacson believes it’s important to encourage Senate and Congressional Democrats who have risen up and made headlines, such as Senator Chris Van Hollen (Maryland). In April, Van Hollen requested a direct meeting with Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran citizen living in Maryland who was deported to El Salvador in March despite a 2019 court order barring his removal due to fear of persecution.

“Democrats will benefit politically from continuing to rightfully make a lot of noise on this issue,” he said. Isaacson added that Americans should also write to moderate Republicans who are expressing subtle concerns about enforced disappearances, to convince them to act.

“We all need to continue to make our voices heard on this issue,” he said. “Keep protesting, keep writing about it, keep calling your legislators.”