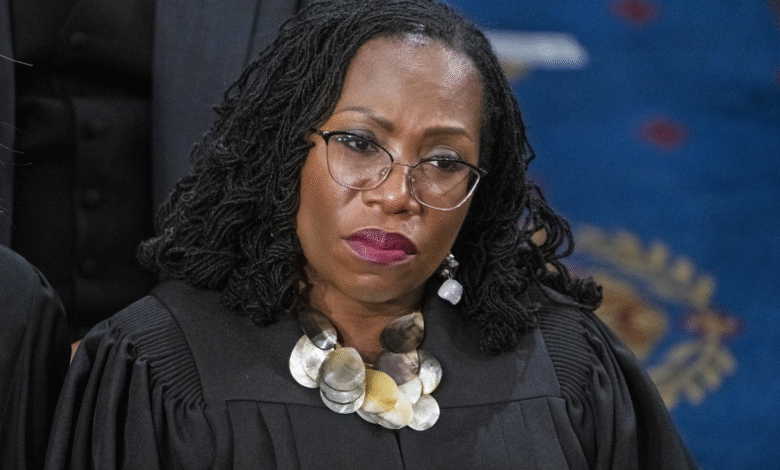

Ketanji Brown Jackson Calls Out The Conservative Supreme Court Justices As Partisan Hacks

Supreme Court justices often spar in opinions, but Justice Jackson’s plain critique of her conservative colleagues is striking.

Supreme Court justices regularly exchange sharp barbs in their opinions and dissents, but it is rare for a Supreme Court justice to explicitly characterize their colleagues as partisan zealots. Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson did precisely that in her dissenting opinion regarding President Donald Trump’s revocation of National Institutes of Health grants.

The Court’s split decision in National Institutes of Health v. American Public Health Association, issued Thursday, focused on whether the association, 16 states, and other plaintiffs could challenge Trump’s revocation of the grants, calling it “arbitrary and capricious” under the Administrative Procedure Act, the law that governs the conduct of executive agencies.

Five conservative justices—Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—issued an emergency opinion, without argument, holding that the plaintiffs could not sue to recover revoked funds in federal district court but must file their case in the Court of Federal Claims for damages. Meanwhile, five justices—John Roberts, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Barrett, and Jackson—ruled that actions challenging agency decisions under the Administrative Procedure Act could be brought in district courts.

Jackson, a nominee of former President Joe Biden, wrote in her dissenting opinion that the conservative majority’s decision to reject claims court challenges amounts to a “bizarre system of divided claims” that weakens judicial review of grant rescissions by sending plaintiffs on a futile multi-jurisdictional quest for full relief. She added that the conservative justices had transformed “a nearly century-old law, designed to address wrongful agency decisions, into a challenge rather than a remedy.”

The Court had no clear reason for holding this way. But this decision is consistent with recent decisions by conservatives on the Court to support the Trump administration in cases involving extraordinary claims of executive power by requiring plaintiffs to undergo complex and novel legal procedures to obtain relief. Jackson was careful to emphasize this.

More broadly, however, today’s decision is in line with recent trends at the Court. As Jackson writes: “While the judiciary should do its best to uphold the rules of law, the Court has chosen to make it as difficult as possible to defend the rule of law and prevent clearly harmful government actions.” This is Calvinball jurisprudence, with a nuance. Calvinball has only one rule: there are no fixed rules. It seems we have two options: one or the other, or this administration always wins. The game “Calvinball” is a game from the Calvin and Hobbes comic book series, where the only rule is that the players make up the rules as they go along, and Jackson explicitly portrays his fellow conservatives as partisan scum inventing laws to help a president of their own party.

This “Calvinball jurisprudence” has been the hallmark of Roberts Court opinions during Trump’s second term. In CASA v. Trump, a birthright citizenship case, conservatives blocked district courts from issuing nationwide injunctions, which would have forced the plaintiffs to return and file class-action lawsuits, a practice few conservatives also considered impermissible. In JGG v. In v. Trump, the court ruled that the Trump administration must provide due process to immigrants detained under the Alien Enemies Act, but required that these immigrants individually exercise their due process rights through habeas corpus.

Conservative justices have also used emergency, or “shadow,” filings to allow various Trump administrations to… implement policies that apply while cases are pending in district or appellate courts, although they are largely irreversible if the plaintiffs prevail. These policies include Trump’s purge of the federal civil service, the decertification of federal government unions, and the firing of employees from several member agencies.

Although some of these cases, such as J.G.G. and CASA, have allowed plaintiffs to obtain compensation, even after navigating a maze of courts, Jackson argues that the court’s erroneous decision in the NIH case does not provide schools, states, researchers, scientists, and healthcare providers with such a remedy.

By distinguishing “grant termination from review of the termination policy,” the court’s decision “creates a mirage of judicial review while defeating its purpose: to redress harm,” Jackson writes.

It achieves this by empowering federal courts to rule on Administrative Procedure Act (APA) claims that grant revocations are “arbitrary and capricious,” but it does not allow them to reinstate revoked grants. Plaintiffs must therefore file their claims in the Court of Federal Claims. Claims courts can only award damages for breaches of grant contracts. But in this case, the plaintiffs are not seeking damages; rather, they are alleging that the administration abused its statutory authority and that the revoked grants should be reinstated. It therefore seems highly unlikely that the plaintiffs will be able to obtain the relief they seek.

Jackson writes: “After today’s order, how can plaintiffs like these—recipients of federal grants who believe their grants were terminated due to an unlawful policy—obtain full compensation?” “The court didn’t answer. The answer seems to be: they can’t.”

What the conservatives have created here is a system of judicial review in which plaintiffs can prevent future revocations of grants to non-plaintiffs, but cannot recover their already revoked grants. Jackson points out that this is the opposite of how courts are supposed to decide: “Not long ago, the Court insisted that the ‘parties’ principles, which permeate our conception of fairness, require courts to grant ‘full relief’ to plaintiffs and none to non-plaintiffs.”

More bluntly, conservatives approve of Trump’s revocation of hundreds of millions of dollars in grants for scientific and medical research.

And they do so even though there is no need to decide this case. Jackson persists in criticizing the conservative majority for choosing to decide this case. She cites, in particular, Kavanaugh’s insistence that “we must decide the motion.”

Jackson writes: “Justice Kavanaugh’s suggestion that the Court should rule on the relative interim standing of the parties when presented with an emergency motion… is without merit; it is not supported by any Supreme Court procedural rule.” Moreover, viewing our role as mandatory in petitions of this nature contradicts decades of practice.

Jackson points out that the Court’s Calvinball-style precedent would have disastrous consequences: “The progress of scientific discovery will not only be halted, but reversed.” This is what happens when you invent rules in the hope of winning.